Over the past year I've been experimenting with training formats. Some practices just can't be mastered in a two-hour workshop and require mentoring for some time before the participant can actually use the technique alone. Even worse: many details won't be conveyed in such a short time.

The typical solution is daily (technical) team coaching like the Samman method promoted by technical agile coaches like Emily Bache and Llewellyn Falco. However, this requires the initial interest and availability of a full team, which is often hard to get.

This is why at my client Worldline (previously Ingenico) we started what we called an internal software craftsmanship bootcamp. The idea would be to invite people from any development team to join every other week for half a day and work together on a project following all the agile and software craftsmanship best practices. Learn from a real project experience with real constraints while still having all the time to learn new practices.

In this article, I'll share with you what we learned from that. Not knowing what could be of interest to you, many practical details are provided for all sorts of aspects of the activity. Feel free to skip and read only what you want of course. ;-)

In order to garantee high quality coaching, it was only possible to welcome a small group of 5 participants, which is a big limitation for a department of almost 100 developers.

Luckily, management was very supportive for this continuous learning initiative and wasn't scared of letting these employees spend the equivalent of an extra full day of work every month on learning. Convincing the developers to invest their time was actually more difficult! :-) I suppose this could be caused by teams thinking they are expected to deliver just as much even when they attend trainings...

As I said, I wanted to go further than just theoretical exercises and be able to provide guidance in applying the techniques on an actual project. In order to justify the time investment to management and to the participants, I felt it was better to go for an actual, useful project. Some new in-house developer tool or something like that. This would also make us face all the challenges of real production applications (well, almost, because it was still an internal tool with no critical usage). At that time I was pushing for having metrics on the development and delivery process, so it became our first objective: make a web app that would show the number of deployments of each of our micro services per month.

This "real project" gave a lot of motivation to the participants to keep going on for almost one year. Even more so when potential users were asking if they could try it out already. It also justified focusing on actually deploying every small increment, not for the sake of learning but because we wanted to show something!

My main concern by teaching on a "real project" was that we would spend much time on things that are far away from the topics I wanted to promote (like TDD). This is why I had prepared a walking skeleton of the application (meaning an empty, but running service with a pipeline to deploy it). This way I hoped partipants could just start adding their code in it and not worry about the plumbing.

This turned out not to be enough. This is my most important learning: yes, we did spend a riduculous amount of time on areas that I didn't want to focus on because they were necessary to make that service actually work. For example, the team had to learn how to setup and deploy a new database with the in-house self-service platform (none was foreseen at the beginning of the project). Facilitating collaboration on that topic is not useless, but it meant several sessions without anything related to actual code. Note that participants were happy to have learned how to do that at Worldline as it could be useful for them in their other projects in the company, it just wasn't in line with my goals. :-)

Another big investment in time was exploring and understanding the quite unintuitive API of our deployment tool (Octopus Deploy). Again, we tried to see this as an opportunity to learn how we could collaborate on a "research" activity, but it was still much time wasted on reading documentation and try & error with the API before anything worked. Not your best way to introduce mob programming to the group and convince them to do more of it. :-)

Following coaching tips offered by Llewellyn Falco & others, each session consisted mainly of mob programming, followed by a short retrospective.

As often, we had many discussions about the time for our mobbing rotations. I insisted on keeping it short (5 minutes) in order to keep everyone engaged (not staying too long in a role in which you may be more passive or distracted). Remote setups are even more challenging in terms of attention so this was my main concern. That said, I couldn't refuse to experiment a longer time of course. :-) So for the last couple of sessions we extended that time to 8 minutes, which seemed to please most participants. I would blame it on the switch not being seamless enough, but we kept it like that.

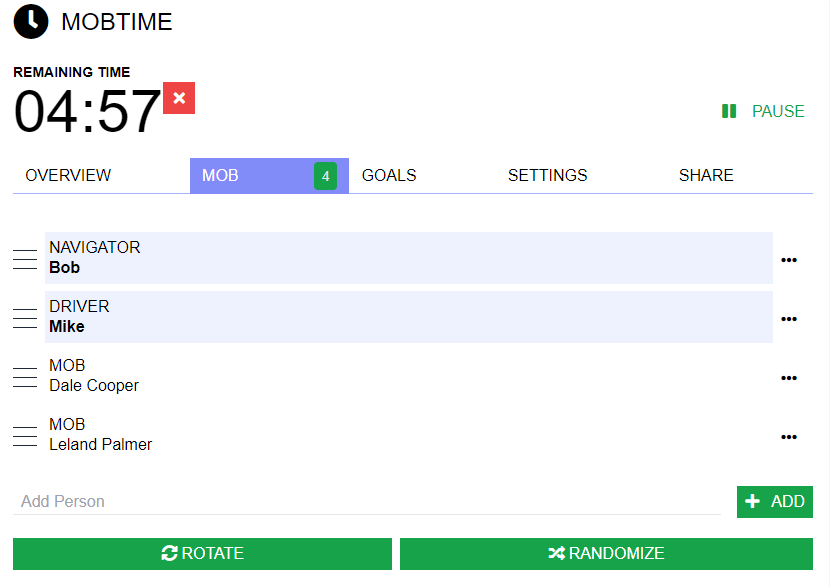

Being remote brings another challenge : it's quite hard to know who sits on your right for the rotation. :-) That's why we used a tool (Mobtime) to list all mob participants and to tell us to switch every x minutes and indicate who had which role then. Quite handy, although we had many sync issues with it. Also, being able to keep our configuration from one week to the next would have been even better. In case you try it, be sure to activate the sound for the timer and share your sound via Teams so nobody misses it. ;-)

I wanted to focus on learning some theory along the way, but still avoid ex-cathedra explanations on random topics that people forget right away because it wasn't really relevant to them. For this reason, I didn't plan any theory session and instead jumped on every occasion to explain something related to what we were doing at that time. It could be big things like TDD or hexagonal architecture, but also small details like humble objects or even the new shortcuts we used in our IDE! I had very positive feedback about that.

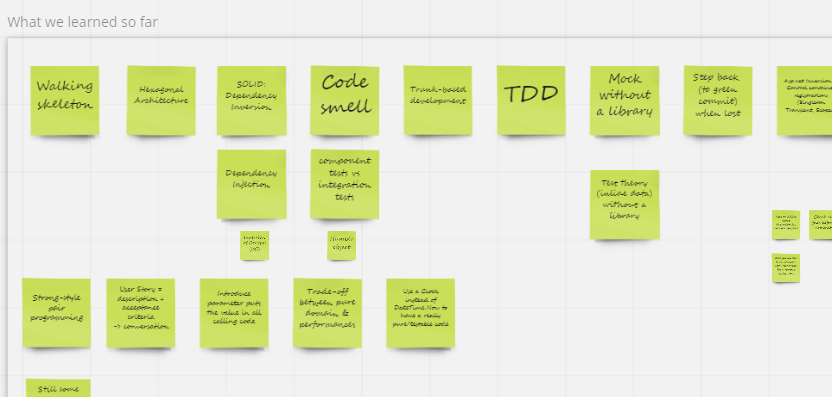

As repetition is the mother of learning, we used a Miro board on which we would add stickies every time I would explain some theory. I would then start every sesssion by asking each participant to pick one sticky note that they felt was interesting for them and to try to explain it to the others. The rest of the group would help if needed. They would select concepts new to them, but also often things they already knew but realize they didn't know it enough to be able to explain it to someone else, which would be even better in order to be able to use this concept in their daily life.

The feedback on that practice was excellent and I'll certainly keep doing something similar wherever I can.

It started working less at some point when nothing new was available on the board and I offered participants to skip it in order to avoid reviewing the same things again and again. :-)

I suspect not having anything new on that board for several sessions meant we were not doing great in terms of learning (although not always doing something new but instead using things we saw before is perfectly fine). More on that below.

As already stated above, having maximum 5 participants is a big limitation in such a large department and management questioned on some occasions this long-term focus on only a couple of employees. It clearly doesn't scale and excludes most people from the initiative. The lack of visibility that comes with this situation made this activity much less interesting for management than other very visible events I organized.

Six months later, a manager asked that we consider onboarding 2 new members who were eager to learn more. At that time we had 4 participants (one had dropped out very early, officially because of agenda conflicts) so the whole group accepted to take the risk of working with a bigger mob and having less time as typist or navigator. As often is the case with mob programming, they were onboarded in no time and managed to participate from the very first session. The fact that they lacked some knowledge from the previous sessions was actually an opportunity to let the participants review again their understanding of key concepts like hexagonal architecture etc. by having to explain it to the newcomers.

A couple of months later, after yet another request from management to include more people, it was decided (together with the participants) to stop the bootcamp. The actual request was to onboard other participants, but I wasn't sure what was the best way and I have to admit I wanted to use the time this would free up to try other experiments. :-)

I believe the objective of avoiding a shallow training on TDD and making people aware of what it's like to work with TDD and mob programming was met. After the bootcamp, participants reported being more keen to start doing TDD in their regular projects but not really to try to convince their teams to start mobbing, although the idea was not totally crazy for some.

In the second part of this blog post, we'll cover specific activities and experiments and what we learned fromt that.